Showing evidence

In order to proof that this scenario is possible, two methods were used. A statistical method, and a comparison to the 2015 solar eclipse. In addition other researchers have shown that several <1 GW attacks are also possible.

Statistical method

Using a mathematical model it is possible to estimate the amount of PV energy in a power grid at a given time. Based on this model as well as official sources it was determined that an attack like this is statistically possible. For example, the German power grid can (at peak sunshine times in 2025) cover 50% up to 60% of its power demand using only PV installations. A cyberattack in this grid at the right time could take out up to 60% of the nation’s power supply. Almost instantly causing a very large (nation-wide, up to continental due to the intertwined power grids) power outage.

Sadly, it is impossible to determine exact numbers on the threshold values (though several trustworthy sources indicate a range of 3-5 GW). That said, it cannot realistically be expected of a nation like Germany to lose 50 up to 60% (30+GW) of its power supply instantly and not see a power outage. It is simply too costly for power regulators to have that amount of power balancing on standby at all times. It may even be impossible, to have that kind of reserves trigger instantly as traditional power plants take more time to increase and decrease their overall power output when compared to PV-installations.

Comparison to solar eclipse

Another way of estimating the impact of such a cyber attack, is by comparing it to the 2015 solar eclipse. This solar eclipse happened in the morning when the sun was shining and affected almost all PV-installations in Europe (some more than others). Effectively, the solar eclipse controlled the flow of power from these devices (less sun equals less power from those devices, more sun equals more power from those devices).

The Solar eclipse event was a 2-3 hour long event the power grid regulators were well prepared for. Large solar fields had been temporarily shut off, additional reserves and regulation materials were available, an exact plan of when to regulate in what amounts was calculated based on the expected solar eclipse pattern, extra manpower was available, etc. The power grid stayed balanced that day, due to the effort of all these regulation parties. Had they done nothing, the power grid would have failed without a doubt.

When we compare this to the potential cyber attack it looks very grim. This cyber attack will not take 2-3 hours but +/- a minute. The speed of the peaks and dips will be very hard, if not impossible, to deal with. Besides that, the cyber attack is not something they are prepared for, the additional reserves and regulations are not in place, no extra manpower is present, and no exact plan exists. Another critical point, is that the solar eclipse happened in the morning as the sun was rising. The cyber attack will likely take place in the middle of the day when the sun shines brightest or when the grid is already under extreme stress, increasing the impact of controlling the flow of these devices. Then finally, the solar eclipse follows a perfect logical pattern. A cyber attack can follow any pattern the attacker creates. This may in fact be random, or shifting between on and off very fast. For example causing several GW swings per minute. It becomes nearly impossible for power grid regulators to deal with this as it follows no expected pattern and the attacker is capable of controlling the flow faster than the grid regulators. The below shown graph is an example, but the pattern may very well be much more random, with far more peaks and dips than shown below.

Based on this comparison it can be concluded that the cyber attack is far worse. Any power grid with a lot of PV power in it will be affected heavily. Due to the intertwinedness of power grids, large scale power failures can, and should, be expected.

Based on both the statistical information and the comparison to a real life scenario it can be concluded that this type of load-altering attack is indeed theoretically possible.

Alternative <1 GW scenarios

In addition, a recent australian research paper also indicated that control of <1 GW of PV systems may already pose a major issue when a grid is under stress.

The key findings in that research paper relevant for these attacks, is that you do not necessarily need to completely drain the reserve pool, you just need to give it the final push and it’s possible to accurately predict when the grid is already in trouble.

Furthermore, it indicates that the speed at which the inbalance is caused also matters greatly. As long as you can cause an inbalance faster then others can remediate it, you can still trigger cascading failures even with <1 GW attacks.

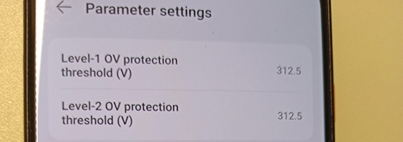

Finally recent changes to PV-installations often allow setting sensitive and critical electricity and safety parameters using default available features (often even via cloud environments). These parameters can often be set to dangerous values, causing all sorts of electrical problems (over or under voltage, oscillations, reactive power manipulation, hindering recovery etc.), both locally and in upstream substations.

Hence the latest insights indicate that having access to even a relatively small amount of PV-installations enable an attacker to cause major issues in the grid.